What to do with what was done to us

Everything I read in August 2025

Our first-ever Zoom Book Chat is this weekend - Sept 6th at 1 PM Central! We'll talk about how our reading is going + what plans we have for the rest of the year. This session is just for paid subscribers, I will email the zoom details tomorrow. I’m offering a special 25% discount through Sept 6 for anyone who wants to join. Please come!

In Sad Tiger — a memoir of surviving childhood sexual abuse — Neige Sinno titles a chapter What to do with what was done to us. Many of us carry this question as we move about the world, doing our best to simply keep going and not fall through the abyss that threatens to engulf us. The books I read in August seemed to be circling the same terrain.

These stories were not about new beginnings or fresh starts so much as the long aftershocks of what has already happened. They were about grief that touches every atom of your being, about lifelong friendships that both wound and sustain, about the humiliations and betrayals of girlhood that refuse to stay buried, about the invisible systems whether capitalism, patriarchy or the influencer economy that press their weight onto our bodies and choices.

While much of this body of work felt quite different in texture, the writers of these stories shared a certain willingness to hold the gaze. They offer no neat resolutions1, preferring instead to sit in the tension of aftermath: how to live when something essential has been lost or broken, how to make meaning without the promise of repair. What to do with what was done to us. Again and again… no real healing nor vindication, no erasure nor denial but instead a strange and fierce kind of persistence through empathy, through writing, through the torturous work of simply keeping on.

I cried many tears while reading this month… but I have to be honest with you, nothing makes me feel more alive than being WRECKED by a book… and this whole month was a heartbreak in slow motion. I loved every little minute of it.

📚 Books mentioned:

Ghost Fish — Stuart Pennebaker

Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay — Elena Ferrante

The Wall — Marlen Haushofer

A Girl’s Story — Annie Ernaux

Leverage — Amran Gowani

The Story of the Lost Child — Elena Ferrante

Sad Tiger — Neige Sinno

If You’re Seeing This, It’s Meant for You — Leigh Stein

📚 Ghost Fish — Stuart Pennebaker

Alison, 23, moves to New York City after the tragic loss of her younger sister, her mother and her grandmother. Grief shadows every step she takes until one night she comes home from her restaurant job and finds a ghost fish. She instantly recognizes it as her sister and begins carrying it everywhere, tucked in a pickle jar. What sounds absurd on the surface becomes moving and believable in Stuart Pennebaker’s debut. The ghost fish is both comfort and burden, a stand-in for magical thinking and for the stubborn ache of loss. The novel is tender and humane… its weirdness grounded in sadness and love. A book about debilitating grief, friendship and radical empathy, it inspired me to draw a list of other books I have loved that have felt similarly tender with a touch of weird and invited you to share your own:

Be sure to check out the comments under that post because you guys came through strong with a list of fantastic recommendations AND please continue to support debut authors who historically don’t receive the same level of publicity support from publishing houses as more established authors.

📚 Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay — Elena Ferrante

After binging through volume 1 and 2 of The Neapolitan Quartet in June and July, there was no stopping me now. For anyone who tried My Brilliant Friend and thought it was OK… please believe me… the story gets better and better as the series progresses. Which, by the way, is exactly the kind of thing that people say to me about On the Calculation of Volume and I still resist. So… you won’t hurt my feelings BUT if you are curious, just have that little tidbit in your backpocket.

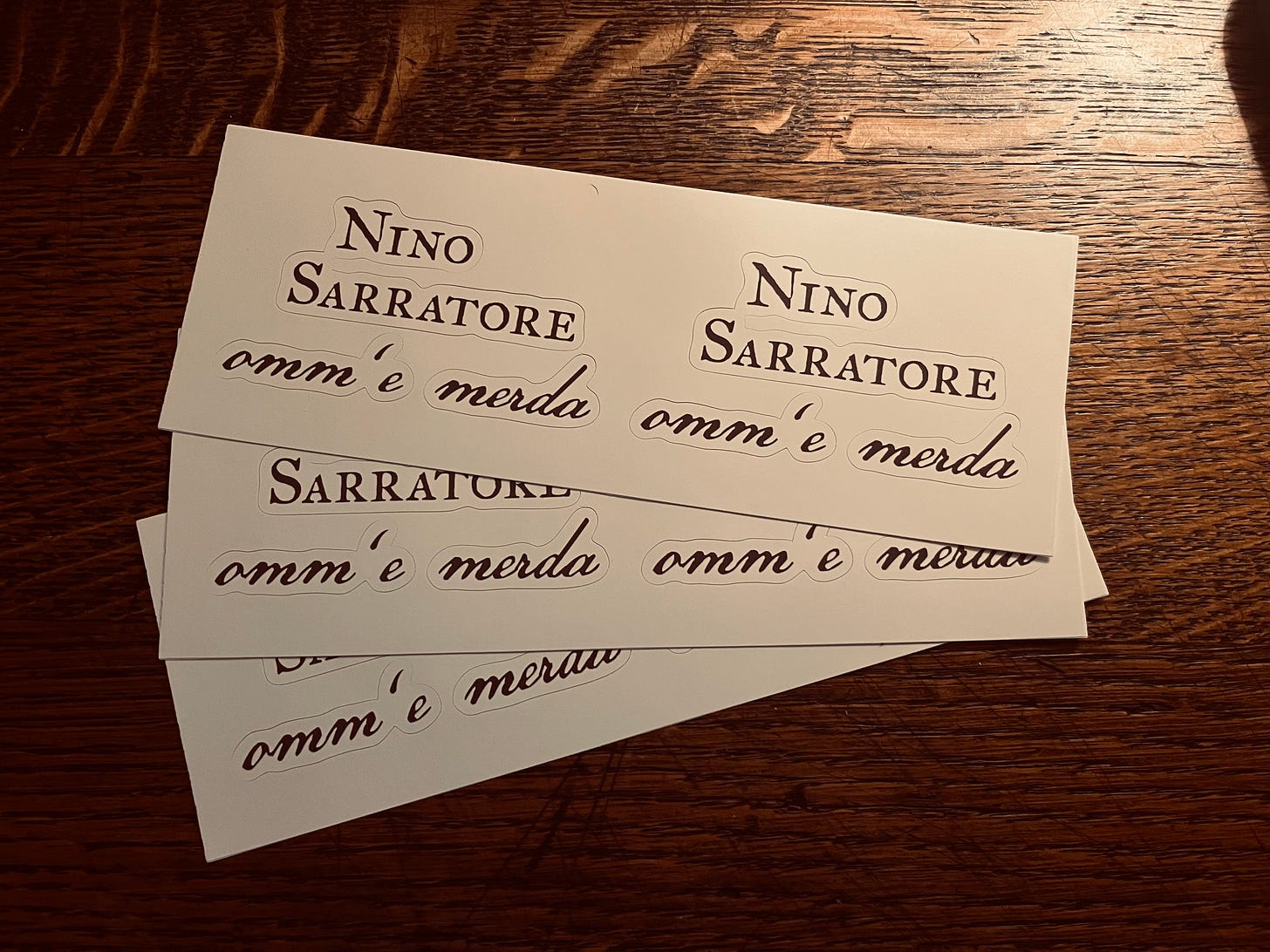

The third Neapolitan novel follows Lila and Elena into adulthood and Ferrante spares no one. Lila is working in a meat factory, her marriage behind her but the weight of class and circumstance pressing down harder than ever. Elena has published her first novel and seems poised for escape not without the help of her in-laws but Ferrante quickly shows how fragile that kind of liberation can be. Ferrante brings back Nino Sarratore to ruin your reading days — Fuck Nino Sarratore — and said developments will have you questioning how so many smart women end up losing their minds over immature self-centered men-children who are unable to grow up.

In this particular book, Ferrante is pure perfection in the way she writes about female ambition and solidarity, about women helping each other, covering each other’s tracks… Also, about the competing forces of our professional drive, sexuality, familial instincts and the constant string of compromises we make in order to belong. This volume left me both exhilarated and gutted. Ferrante is a master of making you so mad at her characters while also filling your heart with complete and total devotion to them. The final chapter made me feel so angry and strung out, I knew I would need to take a break from the series.

📚 The Story of the Lost Child — Elena Ferrante

Aaaaaand… that lasted for about 24 hours…. I had to read the last book. (My review will include minor spoilers, I am trying NOT to spoil everything… but don’t let me ruin this for you).

Ferrante closes the Neapolitan quartet with a novel that is both epic and devastating. Elena returns to Naples with her daughters, flush with literary success and swept up in a romance that will eventually devastate her. Time speeds forward and we see her becoming a celebrated author but her literary ambition is tangled with the guilt and regrets of motherhood… Her writing never quite seems to impress the ones that matter to her the most, the judgment and criticisms unrelenting. Lila too has fashioned success through entrepreneurship, yet finds herself enmeshed in the corrupt, chauvinistic forces she once resisted. Elena clocks their petty rivalries, their disappointments with one another… yet, the two remain each other’s deepest companions.

The book’s title refers to more than one lost child. Literal tragedy strikes both women but there is also the figurative loss of the selves they imagined they might become. Naples with its violence, corruption and vitality is a constant presence, shaping their choices and eroding their illusions.

A had a big, BIG cry when I finished the book. The day that followed felt just so sad and mournful. It took me a while to realize I was grieving the fact that I had left the world of that book and even if I chose to reread it, it would never feel the same. As I’ve shared with some of you already, I didn’t even feel like I was loving it all that much while reading…. but the effect of the quartet as a whole was completely overwhelming, in the best possible way. I felt so at one with the characters, with their faults and triumphs…. I kept wishing for one or all of them to catch a fucking break… but that’s not what life is, is it? A life lived to its fullest is the time you spend catching your breath while getting from one crisis to another. No career, no relationship, no friendship is perfect and yet if we are lucky, we experience moments of profound clarity and connection that help carry us through the hard parts.

Still in mourning that this one is over — reading The Neapolitan Quartet is definitely one of the highlights of my reading year so far. Because of it, I have also found myself feeling deeply connected to other readers in a way that I don’t believe I’ve felt before. From my ongoing therapy sessions with , general commiseration with to getting ideas on how to extend my stay in the NQ universe by and tracking down some superfan stickers thanks to … I felt in many ways the way that Lenu and Lila felt through most of those books — understood and carried forward by the force of female friendship — which was probably the biggest gift of all.

📚 The Wall — Marlen Haushofer

This book had been on my radar for a long time but after reading and loving I who have never known men by Jacqueline Harpman last year, I didn’t feel urgency to pick it up because it sounded too similar. However, after reading ’s review of it, I just had to… and I am SO GLAD I did. It was definitely my favorite book I read this past month and… it may be my favorite book I’ve read this year, so far.

A middle-aged woman is vacationing at a hunting lodge in the mountains of Austria. One day she wakes up to discover an invisible wall cutting her off from the rest of the world. Everyone on the other side appears to be dead, frozen in time, and she is left utterly alone with only a dog, a cat and a cow for company.

The novel is spare and unsentimental, the narrator documents the daily business of survival like she’s reporting on the weather or on a sports game. But the narrative builds up to a deeply moving reflection on what makes a life worth living, the gentle beauty of routine and the fragile comfort of caring for animals and the land. Reading it felt almost meditative, an inquiry into solitude, resilience and the strange ways companionship manifests. For those of you who, like me, are not massive sci-fi or dystopian fiction fans, do not let the premise put you off. The wall itself is less a sci-fi tool than a metaphor about isolation, gender and what happens when the scaffolding of society disappears. Haushofer is not interested in telling you what happened but rather what happens to a person when all the invisible threads that kept them tied to family, children, life dissolve. Who are we when nobody is watching?!

In a month of total heartbreakers, this book is the one that I found the most profoundly devastating. It made me feel so much but, most notably, it grew in me a sense of almost-longing for solitude and quiet, for time away from modern capitalist bullshit, for a simple, regulated existence in alignment with nature and animals (sweet gentle souls).

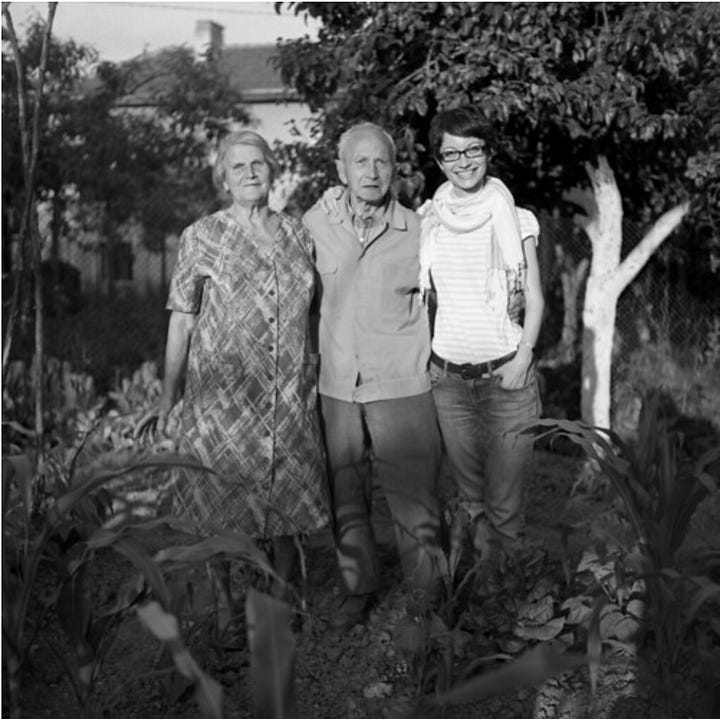

It also made me feel so much belated understanding and relief for my grandparents — now long deceased. Both my mom’s and my dad’s parents lived simple lives, in villages away from the hustle and bustle of modern cities, away from politics and professional ambition, away from money and achievement. This book made me remember how much love they all always seem to feel for their land and their animals. As a young person, I could never quite understand or accept that. I often diminished that love and also assumed they lived lives full of regret. For what could be more sad and boring than all the things they did each day to care for their gardens and their animals.

This book made me realize how much love and peace their life contained and how patiently and consistently they tried to convey that but I refused to see. Reading this story felt so cathartic for me, it really felt like it flipped a switch in me that helped me SEE the facts of my own life in a completely different light. It gave me both clarity and closure that I did not even know I had been searching for. I loved it so much. So so much. Marlen Haushofer’s Killing Stella is already on deck for me to read this September.

📚 A Girl’s Story — Annie Ernaux

In keeping with my goal of pursuing more monographic reading, I picked up A Girl’s Story — my third Ernaux since I started reading her in January! I read this book with and felt so grateful to have a thought partner in this one as it stirred up A LOT of residual anger in me. Thank you, Grace, for helping me process!

In this memoir, Ernaux returns to the summer of 1958 when at 18 she leaves home to work at a camp and quickly proceeds to lose her virginity to one of the more senior camp counselors. The sexual encounter is traumatic for a multitude of reasons, leaving her to endure a profound, isolating shame that lasts her a lifetime.

The shame begins with the pivotal night of her first encounter with H., which is deeply transactional and devoid of mutual respect. Ernaux, who is just 18 at the time and naive, has developed an intense crush on the popular, older male counselor. Their night together ends in an ambiguous sexual act — it reads like it was consensual but also quite crass and forceful… After their night together, he quickly moves on. She is left feeling completely used and without the connection she desperately desired.

~60 years later, Ernaux later reflects on that event with a complex sense of shame. Rather than seeing herself purely as a victim, she feels humiliated by her own "complicity" in the situation. Her intense desire for H.'s attention and the pride she feels in being chosen by him make her submit to his will, and she feels humiliated by her own acceptance of this treatment.

The aftermath of the encounter is where the humiliation truly solidifies, as her personal experience becomes public knowledge and a topic of scorn. The morning after the encounter, Ernaux is ostracized from the camp community. Both male and female counselors begin to insult her, calling her a slut. In her desperation to escape the unbearable feelings of shame, she engages in reckless, self-destructive behavior, laughing it off and engaging in promiscuous behavior — an attempt to define her sexuality on her own terms, but also a way to punish herself.

The adult Ernaux copes by burying the memory of "the girl of '58" and attempting to create a severance between her past and present self. So much so that she even writes the novel in the third person. For a long time, she also refers to her past self as a "nothing girl," an attempt to diminish the pain by diminishing the person who experienced it. Ultimately, Ernaux’s writing becomes her coping mechanism. She realizes that the act of revisiting the event with a writer's eye, trying to bridge the 60-year gap and be objective, becomes her way of reclaiming her story.

I am not sure if my summary does this book justice. It’s not simply a memoir, it is an excavation. She goes bit by bit and documents all the awkwardness, the cruelty, the sense of being swept along by others’ perceptions and desires. She makes no excuses for the naivite, but eventually is able to find self-compassion when she realizes that sometimes in life, we end up giving outsized significance to people who do not deserve it.

I don’t know if you can tell but I personally feel no tenderness for my high school years and this book transported me to that time in high school when you feel so fucking ready to fall in love, to be a WOMAN lol, to find your people…. And you are just this blob of feelings, seeking people to attach to… It’s so pathetic in a way when you look back on it, but it feels so raw, desperate and urgent at the time. I think this book was a love letter to that past self, treating her experience with the seriousness it deserves, registering the casual cruelty of it all… but also locating a sense of peace around it. As brutal as it was, this book felt quite vindicating.

My favorite Ernaux so far.

📚 Sad Tiger — Neige Sinno

Sad Tiger was the book I almost did not want to read knowing how difficult its subject matter would be. But when Lauren Elkin recommends it and Annie Ernaux blurbs it… what are you to do?!

Neige Sinno writes about surviving childhood sexual abuse between the ages of ~7 and ~14 at the hands of her stepfather, weaving memoir with literary criticism, cultural studies and philosophy. The book is harrowing but also incredibly cerebral, insisting on thinking through pain rather than emoting around it. Sinno threads her own story through readings of writers like Nabokov, showing how literature both illuminates and obscures abuse. The prose is sharp, vulnerable and at times unbearably raw.

Earlier today I was scraping dried up oats from the bottom of a breakfast bowl and was struck by how similarly Sad Tiger felt. In telling her story, Sinno has not only emptied the bowl of its contents but is determined to do everything in her power to describe, analyze and generate insight from every little spec that formed the experience of her abuse. The account feels detailed, exhaustive / exhausting, clinical and borderline psychic. I would read transfixed and would begin to feel a question forming around an aspect of her ordeal and before I knew it, Sinno would be tackling it with an intensity and a commitment to objectivity that felt both shocking and illuminating to read.

Sinno writes movingly about indescribable terrors. She describes being victimized by a family member, a charming abuser who manipulates and hurts her both physically and emotionally. What follows is dissociation, fragmentation of identity, and the loneliness and fear that silence imposes. She stays quiet to protect her younger siblings—who, when their father is finally sent to prison, insist with absolute conviction that he would never have done the same to them.

She later moves to the United States, then to Mexico, where she starts a family. In one unforgettable scene, she watches her husband walk down the sidewalk holding their young daughter’s hand. She realizes she is always watching him—vigilantly, anxiously—to be certain her daughter is safe. And he knows she is watching. That image will stay with me.

I am in awe of Sinno’s conviction in writing her story as memoir — refusing the protection that fiction might have offered. Through the act of writing, she gives voice to the young girl who endured the abuse, a girl who feels at once like part of her and like someone else entirely. Her project is to center the victims, so often isolated and retraumatized by their families’ and communities’ inability to confront their own shame at not intervening sooner. To that end, she weaves in historical research showing that soldiers engage in sexual abuse during war for one reason above all: because they can. Near the end of the book, she admits she feels the same about writing her own story. Why write it? Because she can. Because she fucking can.

I read this book with my friend , though I only picked it up at the very end of the month and didn’t have as much time to discuss it in depth as I would have liked. (Martha, for her part, sent me an eight-minute voice note basically repeating how much she loved it, over and over again!!!) Early on, I told her that Sinno’s style reminds me of Ernaux — and after finishing the book, I feel that even more strongly. Both are willing to go there, to examine themselves with such scrutiny and lack of bias that it almost feels cruel. You want to spring to their defense — no, no, don’t be so hard on yourself, you were young, you didn’t know better. But as you read on, they make it clear: there is no innocence in youth. Children know. Young people know. People do things to us, but we also make choices. And the work is not to excuse or justify, but to write it down as truthfully as possible, then set it aside. Both Ernaux and Sinno insist that “ignoring and forgetting it is not an option, for the more you run from it, the quicker it catches you up.” Yet Sinno also argues, “It is possible to stand back from the brink:”

That is the challenge: how to remain on the threshold of this world, how to keep going like tightrope walkeres along the wire, faacing the future. Wavering, unsteady, but not falling. Not falling. Not falling.

A stunning body of work from Sinno. It is an extremely difficult book to read and I couldn’t recommend it any more highly.

My month of reading was deeply satisfying but also … quite depressing. I was grateful to have committed to reading two new releases that took me out of regular programming and helped me lighten up a bit.

📚 Leverage — Amran Gowani

’s debut novel Leverage is a dark AND funny thriller set in the shark infested world of high finance. Ali “Al” Jafar, a rising star hedge fund manager at Prism Capital, finds himself in freefall when a single botched investment erases $300 million overnight. His boss, refusing to simply fire him, gives Al a brutal ultimatum: recover the money in three months or be framed for insider trading. The clock ticks and Al’s desperation pushes him into morally murky territory, shadowy financial dealings, betrayal and psychological collapse.

I don’t typically compare books to film or TV but this one definitely gave me Industry vibes. Also, it conjured up early 2000s British ensemble film energy — think, Guy Ritchie’s Snatch or Lock, stock and two smoking barrels. Just crackling energy, exaggerated but believable characters and witty dialogue that could have ended up in a pile of cliche but in Gowani’s hands, the story is a total rush to read. It’s sharp without being smug, self-aware without losing substance, and most importantly, it makes you care about the people at its center even as the chaos swirls around them.

Before turning to writing, Amran Gowani worked on Wall Street and it’s easy to see how the experience has informed this book in ways that are hard to measure. As someone who’s worked in corporate America, startups and now sits in a private equity funded cubicle, I felt the most outrageous scenes of the book to be the most believable. And it’s the books specificity that is it’s biggest strength. On a personal note, if you’ve ever been “the only” in a big conference room of suits (or Patagonia vests, take your pick) or felt othered by your workplace compatriots, I think you will find this book especially enjoyable. Because we know how absurd the word of business can feel sometimes (all the time?!)… and what better way to resist the chokehold that capitalism has on us than to laugh at it and punch it in the face?!

📚 If You’re Seeing This, It’s Meant for You — Leigh Stein

Amran’s book paired nicely with ’s latest novel2, which unfolds like a gothic TikTok fever dream. wrote a great review of the book in the context of its being a modern-day interpretation of Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (which, I personally have not yet read).

After a humiliating breakup via Reddit, Dayna, 39, unemployed and career tilting, agrees to help an old acquaintance Craig turn his crumbling Los Angeles mansion into a hype house for influencers. Alongside her is Olivia, 19, a superfan now living under the same deteriorating roof. Their project is to build buzz around the unexplained vanishing of Becca, a tarot influencer whose absence both haunts and powers the house’s content.

Leigh is the queen of social satire and in this book blends surreal mystery with themes of cross-generational cringe, the artifice of online identity and the emotional tumbleweeds of digital fame. The TikTok-ness of it felt a little distant to me, I have to admit… BUT… let me tell you, I felt absolutely transported to my 20s when I took my very own sets of provocative self-potraits and posted them on my personal blog I had built with my own hands in Dreamweaver, inspired by a Swedish-Canadian photographer named Helena Kvarnstrom I had first encountered on Flickr. Illustration below from my personal archive because we are friends and we all need a chuckle, ok. Don’t be jealous of my photography skills, ok? Also, I was 23!!! Be kind!!!

What Stein captures so well is the particular madness of realizing you once had a brilliant idea — that it meant everything at the time — but that its moment has passed. Even as age and wisdom tell you to move on, part of you still clings to the shimmer of that former self. Leigh writes right into that liminal ache, where you’re half-mortified by your younger incarnation and half-tender toward her, because she was the one who dared, who risked exposure, who believed she had something worth saying. The novel becomes less about the influencers or their platforms and more about time itself: how creativity, desire, and self-invention collide with the relentless churn of culture, and how hard it is to accept that what once felt urgent and alive may no longer belong to you.

I spent a whole weekend shuttling between errands and laundry and felt absurdly grateful for the audiobook, which kept me company as I folded. Nobody tells you that adulthood comes with laundry that multiplies at the exact same rate as your ability to avoid putting it away.

As I am scrolling through what I wrote about these August books, I feel like I stumbled upon a good ratio of focus-to-oddball in my reading. 75% of what I read came straight out of central casting for me — think-y women, reflective stories, emotionally heightened states of existence, what is plot?!.. The remaining 25% was current, lighter, plotty and borderline silly… words I typically do not associate with myself. But it felt good to push myself (I am so brave!!! I read funny books!!!)… and it felt great to sense that snap when I returned to my typical. Do you observe a similar ratio? How do you maintain that balance of reading things that you know will work for you vs. pushing yourself a little outside of your comfort zone?

❤️ Favorite books of 2025:

January - Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett

February - Open Throat by Henry Hoke

March - Swimming Home by Deborah Levy

April - Assembly by Natasha Brown

May - The Wilderness by Ayşegül Savaş

June - Checkout 19 by Claire-Louise Bennett

July - Long Distance by Ayşegül Savaş

August - The Wall by Marlen Haushofer

🤓 And to finish, some questions for you!

Which book in your own recent reading has stayed with you most vividly — an image, a sentence, a scene you can’t shake?

Do you find yourself drawn more to books that comfort you, or to the ones that unsettle and press on tender places?

Have you ever read alongside a friend — even loosely, even out of sync — and found that it changed the way you experienced the book?

One of my biggest literary pet peeves is that I hate books with neat endings. It feels so patronizing.

As of Wednesday, Sept 3rd, this novel is also a #27 USA Today best-seller! Congrats, Leigh!!!

"nothing makes me feel more alive than being WRECKED by a book" — you are so right and that is why i'm adding every single one of these to my list

What a beautiful, brilliant assessment. This is one of the best things I’ve read on Substack to date. But I’m new, so I remain hopeful.😉