Issue 105: Why is everybody reading Middlemarch right now?

A hyper-networked, algo-forward world accidentally nurtures something meaningful. Dare I call it a vibeshift?

I will participate, but not as asked.

― Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy

If you've spent even five minutes scrolling through Substack lately, you've probably noticed: everyone seems to be reading the big classics. did a great round-up of book groups and I am personally keeping an eye on conversations around War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov, Persuasion, Pride and Prejudice, Middlemarch, The Iliad, Anna Karenina and Tash's own on To The Lighthouse. THE is reading Middlemarch.

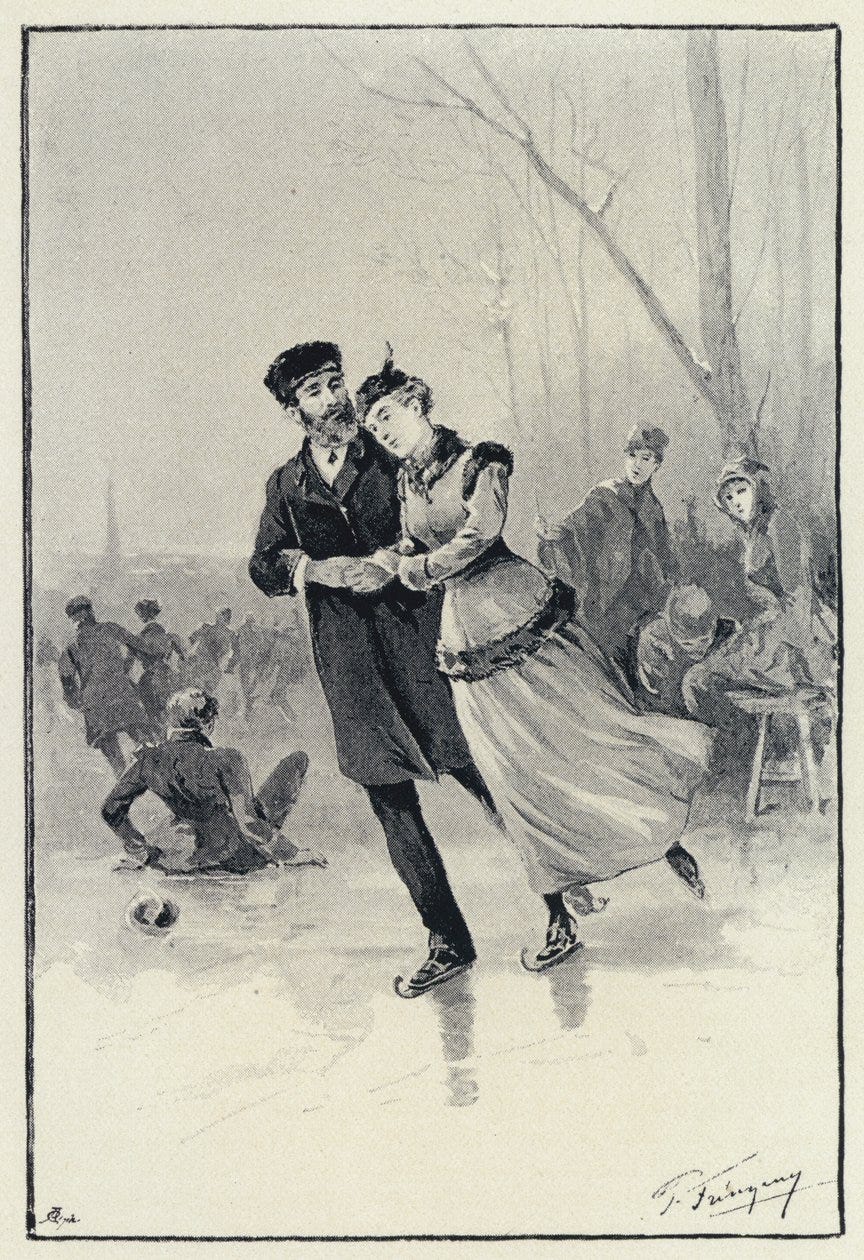

As you know, I love a good reading project and even gave my own a title — 19th Century Wives Under Pressure – diving into Annie K, Middlemarch, Madame Bovary, and The Portrait of a Lady1. I am wildly intimidated but also unapologetically enthused. Reading these books right now feels like the most natural thing to do.

This is the closest to an original trend that I have seen on Substack and, understandably, as more people notice it... we are starting to develop a discourse around it... I really liked ’s take on this. Basically, Naomi argues, publishing is a business focused on contemporary, buzzworthy releases as those sustain literary communities and drive sales. Older classics are often excellent but because their quality is generally assumed the perceived need for critical coverage by traditional publications is reduced. And even though small presses like NYRB Classics or New Directions thrive on reissuing "forgotten" works, their specific aesthetic sometimes invites cynicism. Naomi shared this from Blake Smith which I found both triggering and hilarious:

Those of us who are not in the room, or the groupchat, where decisions about what reputations are to be revived or made can meet the injunctions of the NYRB press with earnest good faith in their latest dispensations ("now is the time to read Magda Szabó—take Agota Kristof away!"); with cautious, sifting, suspicion; or with outright rejection, on the grounds that what the editors declare a "classic" is almost certainly a subcanonical instance of Europe's endlessly dying modernism or its American imitations.

Keep your hands off Szabó, Mr. Smith, I beg you!!!

Naomi acknowledges that while classics are valuable, contemporary books often serve a life-giving function by connecting readers to current cultural conversations and suggests that platforms like Substack are better suited for deep, personal engagement with overlooked classics, allowing writers to share their unique tastes and obsessions, free from commercial constraints.

I think this is absolutely right. But also, building on this argument, I think that the collective push of reading the Classics on Substack is serving that life-giving function that Naomi describes in her piece. There's something different happening here than just individual writers sharing their personal obsessions with old books. When Catherine Lacey drops a note about her Middlemarch reading, when dozens of us are trading observations about Dorothea's choices, when we're collectively puzzling over Pierre's spiritual journey in War and Peace — we're not just reading classics, we're creating exactly the kind of vibrant, current conversation that Naomi attributes to contemporary releases. These aren't dusty book reports; they're living discussions that feel as urgent and relevant as any chat about the latest buzzy release. The classics are becoming our contemporary cultural moment, which is kind of wild when you think about it.

Between our current political anxiety, the endless cycle of late stage capitalist consumerism that readers are not immune from, and the TikTokification of our digital lives, many of us find ourselves yearning for deep thought. Enter the 800-page novel, demanding nothing less than our full attention and promising no quick dopamine hits in return. The parallels between our moment and these 19th-century novels are striking. If you are grappling with reconciling your ambition, your class belonging and your morals – well, look no further. And if social pressure and gender norms have you eyeing the wave of relationship-dissolution memoirs and autofictional novels — divorce-core if you will — that dominated the 2024 literary landscape – may I direct your attention towards Flaubert?

What makes Substack particularly fertile ground for this collective classics obsession is fascinating. Despite the recent influx of users from other social platforms, Substack maintains a distinctive character that seems almost architecturally designed for slow reading. The platform's DNA is built around long-form writing as its primary currency, with deliberately underdeveloped video features2 and an older-skewing user base that still remembers life before the algorithm3. While BookTok serves up snappy 60-second reviews and Instagram reduces books to aesthetic props – with examples of excellence on each of these platforms, absolutely no shade – Substack has organically evolved into a space for deeper literary engagement.

The preference for classics isn't happening in isolation. For one, writers who talk about books on Substack generally over index in their coverage of backlist works. This is not to say that Substack people don’t read current works and new releases, of course not. But anyone who’s spent any time on literary / culture blogs and other publications, on Instagram or BookTok can attest to the fact that the pace here is just different. People read the f-ing footnotes!

In addition, my personal feed is organized around several slow culture communities:

The note-takers obsessively documenting their process, content and materials — creating physical commonplace notebooks in a time when you can literally find any quote you ever needed in a matter of seconds. For examples see: ,

The artists who are not only sharing their work but also building communities around teaching people the intuitive and mind-expanding logic of a regular creative practice: ,

Even more lighthearted discussions around personal style, sustainable fashion and thrifting go deep in a way that Instagram of yesteryear ever did. This ain't TikTok shop, either: , ,

What's particularly intriguing to me in witnessing and participating in all this is how it represents a kind of – to borrow a term from Legacy Russell – positive glitch in the algorithm.

It's a moment where our hyper-networked, algo-forward world accidentally nurtures something meaningful, creating spaces where slow, deliberate engagement isn't just possible but celebrated.

While we often lament how digital platforms can fragment our attention and hollow out our cultural experiences, here we see something different: communities forming around practices that demand patience, attention, and depth.

There's something almost rebellious about choosing to read Middlemarch in an era of endless scrolling. George Eliot's careful examination of provincial life, with its intricate web of human relationships and moral choices, couldn't be further from the quick-hit content that dominates most of our media diet. When you commit to reading War and Peace, you're not just reading a book – you're making a statement about what kind of relationship you want to have with culture and with your own attention.

This return to classics isn't about cultural snobbery or performative intellectualism. Instead, it seems to represent a genuine hunger for works that demand something of us – books that ask us to sit still, to think deeply, to engage with complex characters and ideas over hundreds of pages. These novels, written during another time of massive social transformation, offer us something our current media landscape rarely does: the space to sit with complexity, to understand characters whose actions we might disagree with, to see how individual choices ripple through entire communities.

Perhaps what we're really seeing is the emergence of a new kind of digital literacy – one that doesn't just mean knowing how to use platforms and navigate algorithms, but also knowing how to use these tools to nurture your own deeper intellectual and creative needs. When we read Anna Karenina or Middlemarch on Substack, sharing our thoughts and experiences with others, we're not just reading old books in a new format. We're actively reshaping what it means to be a reader – and a human – in the digital age.

So yes, just like everyone I am trying to read the big classics right now – started Anna Karenina earlier this week and, like , finding it weirder, hornier, and funnier than I'd expected (my January Reads post will be up on Sunday). But more than that, it feels to me that I am figuring out how to read in a way that matters to me, using modern frameworks that engage with these works in ways that enrich rather than diminish my experience. I am finding that doing so is starting to reveal a path toward a more sustainable life online and in a weird way it feels like I am not just reading a novel, I am learning how to pay attention again. In an age of infinite distraction, that might be the most radical act of all.

Leaving you with some questions:

What’s your taken on Substack’s current obsession with the Classics?

Are you member of any of the slow culture communities I mentioned above?

Who are your favorite slow culture Substack writers?

The clever title of my reading project is not my own invention. I saw this very same project referenced in an Amor Towles interview years ago and have been yearning to do it since 2021.

Though this may be changing?

I have absolutely zero data to back this up. Am I see it grown folks around here only because I am old?

Slow reading on Substack might be the first and only time I'm in with the zeitgeist. Thanks Petya!

self promotion makes me physically ill but i do think slowly reading, reading the classics mixed in with contemporary fiction, has sort of been the main point of my whole blog so far??? agree with everything you’ve said here, alongside with the slow realization in later adulthood that i do not have to try and reinvent the wheel every day. we can analyze the wheel and appreciate what it’s doing (sorry for this metaphor).

also middlemarch is an all-time great novel, one of the true masterpieces, of the “i’m so glad i read this as an adult” tier.