Issue 104: The Reading Life of... Celine Nguyen

This one will leave you with a reading list AND the aching desire to upgrade your note-taking game.

When I started thinking about interviewing readers, I specifically wanted to reach out to people who don't work in publishing or write professionally as their main income. I'm fascinated by how people with other careers make time for deep reading and thinking. I'm drawn to anyone who's hanging on tooth and nail to their intellectual life, refusing to succumb to the soulless beat of social media-driven existence, choosing instead to return again and again to books, to timeless wisdom, to ideas. I'm especially interested in people who basically give themselves homework just to have a reason to read what they need.

Nobody fits that profile better than . Looking at the quality and quantity of her writing — both in her newsletter and for publications such as the LARB, ArtReview, and The Believer — you might assume she's a professional writer. But she actually has a big girl job as a product designer. I love Celine's work so much — her singular choice of authors and topics, the emotional charge of her personal essays that somehow still leave you with a reading list, her dedication to amplifying writers whose work she admires. When I sent her my nosiest, nerdiest questions, she answered them all in perfectly Celine fashion: with insight, generosity and a deep set of references to boot.

I'm so grateful to Celine for taking the time, and I know you'll leave this one with so many ideas on how to bring your reading life up a notch.

Tell me a little bit about yourself. What role do books and reading play in your personal life?

Here’s a brief biographical sketch: I grew up in California, and spent my formative years either at the library or in front of the family computer at home. I loved doing little programming projects and playing around in Photoshop, and those things indirectly led to my career as a designer. But reading was always one of the great pleasures of my life. And it’s increasingly how I meet new people and deepen friendships. Reading can be an introverted, isolated activity, but it doesn’t have to be: it can also be a way to encounter other people and their ideas, and discussing books and poetry and essays is fundamentally social!When I was younger, I was tremendously withdrawn and shy—not because I was intrinsically introverted, but because I felt like I couldn’t quite understand how to socialize with people and act “normal.” Instead, I read nonstop.

In high school, I remember going to the library every morning before classes to check out a book, which I would read throughout my morning classes—I was a terrible student!—and then at lunch I’d return the book and check out a new one for the afternoon. Sometimes I’d finish this book too, and get a third book from the library to bring home with me. None of these were capital L Literature—it was all very easy, consumable YA fiction. But it trained me to read often and read for pleasure. And all that gave me the courage, later on in life, to read the more conventionally “difficult” writers and find them rewarding: Proust, Woolf, Bernhard, Kierkegaard…

On an average week, how much do you read and when?

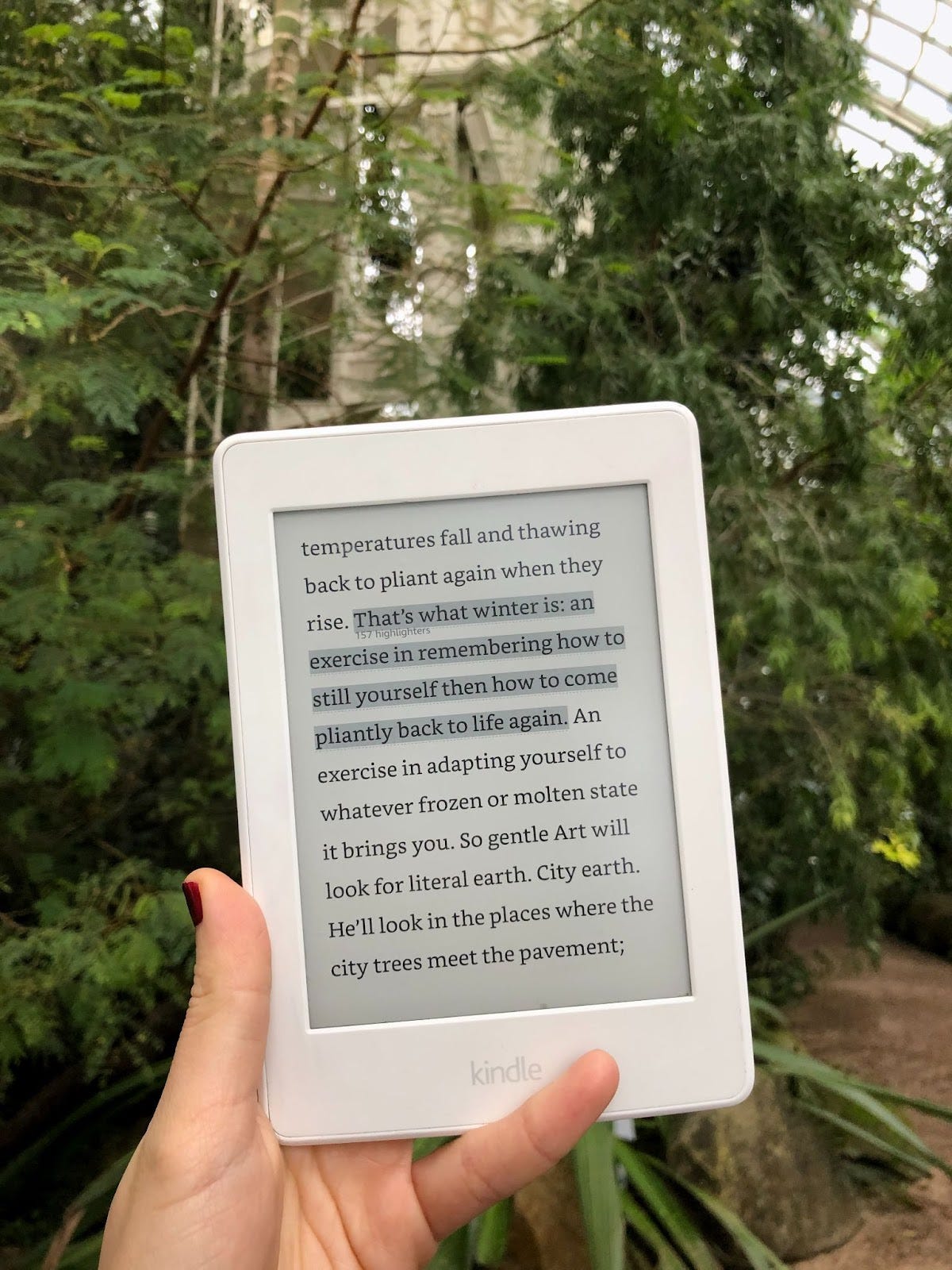

I don’t have a strict reading schedule, but I do have certain rules. I always bring a book with me and (almost) always read during transit. My first job out of college required a long-ish train commute, and I didn’t want to spend 2 hours a day (10 hours a week!) scrolling on my phone. I was also pointlessly cheap at the time—I had a 4 GB data plan and didn’t want to pay for more. So I couldn’t scroll endlessly through Instagram; I needed low-data ways to entertain myself, and reading library books on a Kindle was perfect for that.

In a typical week, I’ll probably read for 5–8 hours in transit: waiting for a bus or train, on the bus or train…and if I’ve arrived at a restaurant early and need to kill time before a friend arrives. I sometimes read before bed, but not very consistently. My favorite weekend morning activity is to laze around with a book and coffee in bed until noon.

But the really intensive reading happens on holiday! My ideal vacation schedule is basically: wake up without an alarm, have a leisurely breakfast while journaling and reading, go to a museum, then find a park or café to read a little more. I usually go through one book every 1–2 days when I’m on vacation.

PKG: Celine’s response reminded me of Lauren Elkin’s comment last year when she told me that interstitial reading counts! This is a recurring theme among the most avid readers I’ve spoken to — don’t wait for some magical moment of calm to arrive so that you can sit down and begin luxuriating in your book. Be a blue-collar reader, read wherever and whenever you can.

What do you like to read? Has your taste changed over the years?

There have been 3 distinctive eras in my reading life. Right now, I read an even mixture of fiction and nonfiction. The fiction I read is typically categorized as “literary fiction” or “literature in translation,” and I’m trying to read contemporary works and great works of the past. For example, I just finished the Polish Nobel laureate Olga Tokarczuk’s latest novel, The Empusium, and in February I’ll probably start the English writer George Eliot Middlemarch, which everyone says is one of the great 19th century novels—I want to understand what’s so exciting about it!

On the nonfiction side, I spent the last 2 years reading a lot of essays, cultural criticism and literary theory (Erich Auerbach’s Mimesis is incredible and really shaped how I read books). I’ve also been reading a lot more philosophy and sociology, maybe because these fields help answer questions like: What does it mean to live a meaningful life? Why do people act the way they do?

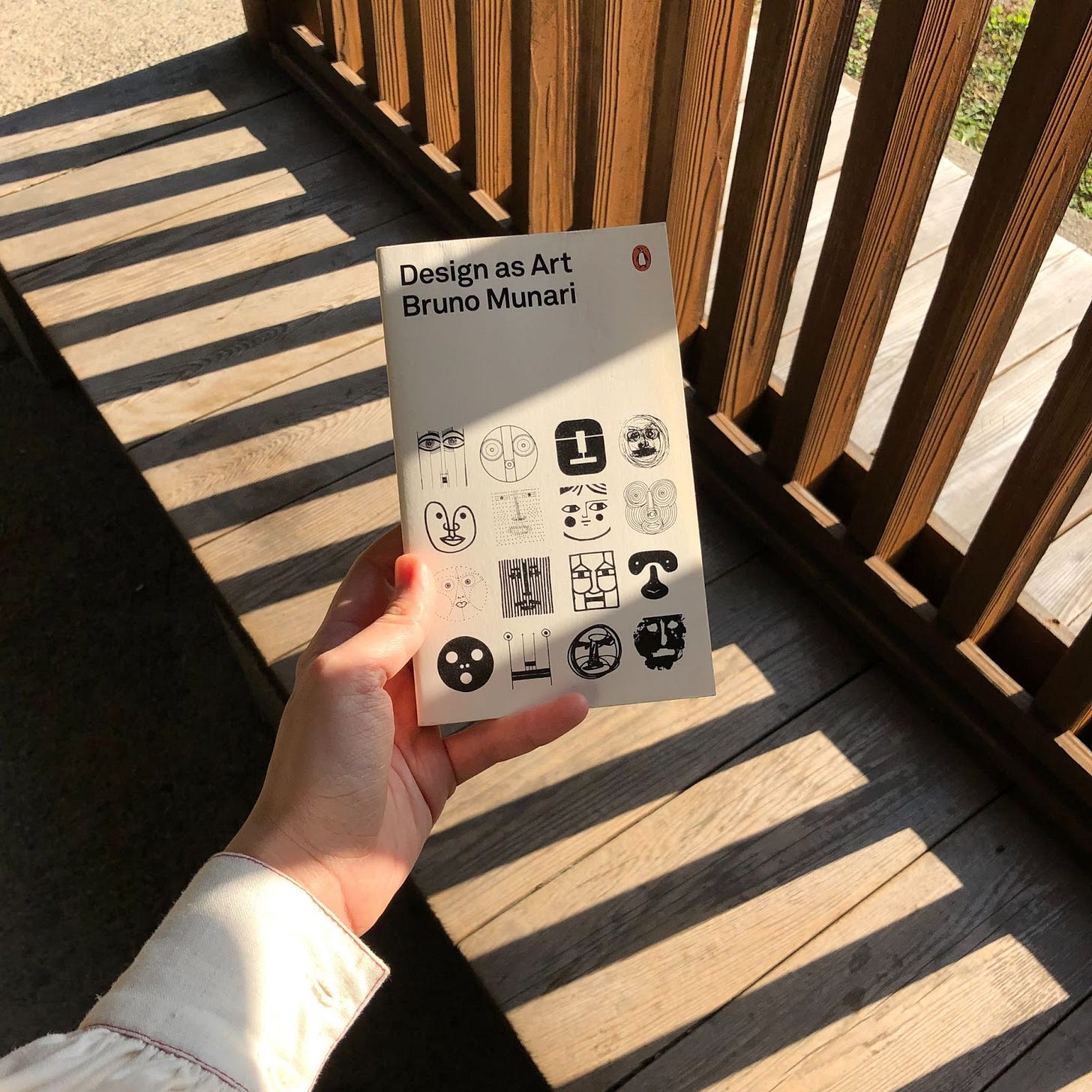

And because my day job is in design—and design is the other great love of my life—I also read a lot about graphic/fashion/industrial/software design, as well as books on architecture and urbanism. I especially love essays from designers where they reflect on their own practice and what it means to do beautiful, sensitive, humane work.

My tastes right now are very different from how I read when I was younger, though! Previously:

Before 18: I had deeply unliterary tastes as a child—I’m fascinated by people who knew, early on, that they wanted to have cool and tasteful reading picks, and deliberately sought out books like David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. I basically didn’t know these books existed when I was younger. When I was in high school, older and infinitely cooler acquaintances would lend me books—I remember being wowed and moved by Margaret Atwood’s apocalyptic novel Oryx and Crake, and Haruki Murakami’s A Wild Sheep Chase—but I didn’t know how to find other books like these. Mostly, I read a lot of YA fiction (I was especially obsessed with fantasy retellings of Greek/Roman myths and Arthurian fables) and a lot of manga. I’m not particularly embarrassed by this; I think it was developmentally appropriate and helped cement reading as a central part of my life.

PKG: Petition to expand the definition of developmentally appropriate reading to mean reading that recognizes the unique needs, interests, and abilities of each child or ADULT.

Early adulthood: In my early 20s, I had this idea that reading fiction was self-indulgent and useless—I read a lot of self-help books, which seemed obviously “useful,” and from 2016–2020, the first Trump years, I read a lot of nonfiction. Those were the years where it seemed like there was a strong ethical obligation to understand American history and world history, and seriously understand the injustices of the world so that you could dedicate a small part of your life to bettering other people’s lives. The books I read then, like the legal scholar Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness and the queer activist and historian Sarah Schulman’s Conflict is Not Abuse: Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility, and the Duty of Repair, really shaped me. I also read a lot about technology and ethics—the political scientist Virginia Eubanks’s Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor was a revelation.

Present: So how, given that history, did I end up here, where I believe that novels really matter and aren’t “useless”? Because now I feel, very strongly, that novels are indelibly important and essential to the project of living—I basically can’t imagine who I’d be without having read Marcel Proust or Qiu Miaojin (a Taiwanese lesbian writer whose writing is so exquisitely emotional and affecting). I’m not really sure! What happened, I think, is that I met a lot of people who I admired and wanted to be more like, and they were so well-read and so eager to discuss the novels they loved, and so I started reading those novels to be more like them.

What's a reading habit you've developed that's unique to you?

I’m one of those rare freaks that really loves reading on a screen, for two reasons. One is that I have terrible eyesight—minus 7 in both eyes—and on a screen it’s easy to scale up the text size! The other reason is that I struggle to pay attention to books unless I’m constantly highlighting passages or making little notes, and it’s easier to do this on an e-reader or laptop.

Physical books are lovely—they’re beautiful objects and generally easier for me to read. But I’ve also lived in a lot of small apartments, so I try to not buy too many books.

Because you have written extensively about your love for research, can you walk us through your note taking method?

My approach to note-taking is extremely chaotic, so I will first explain my note-taking philosophy and then what I actually do.

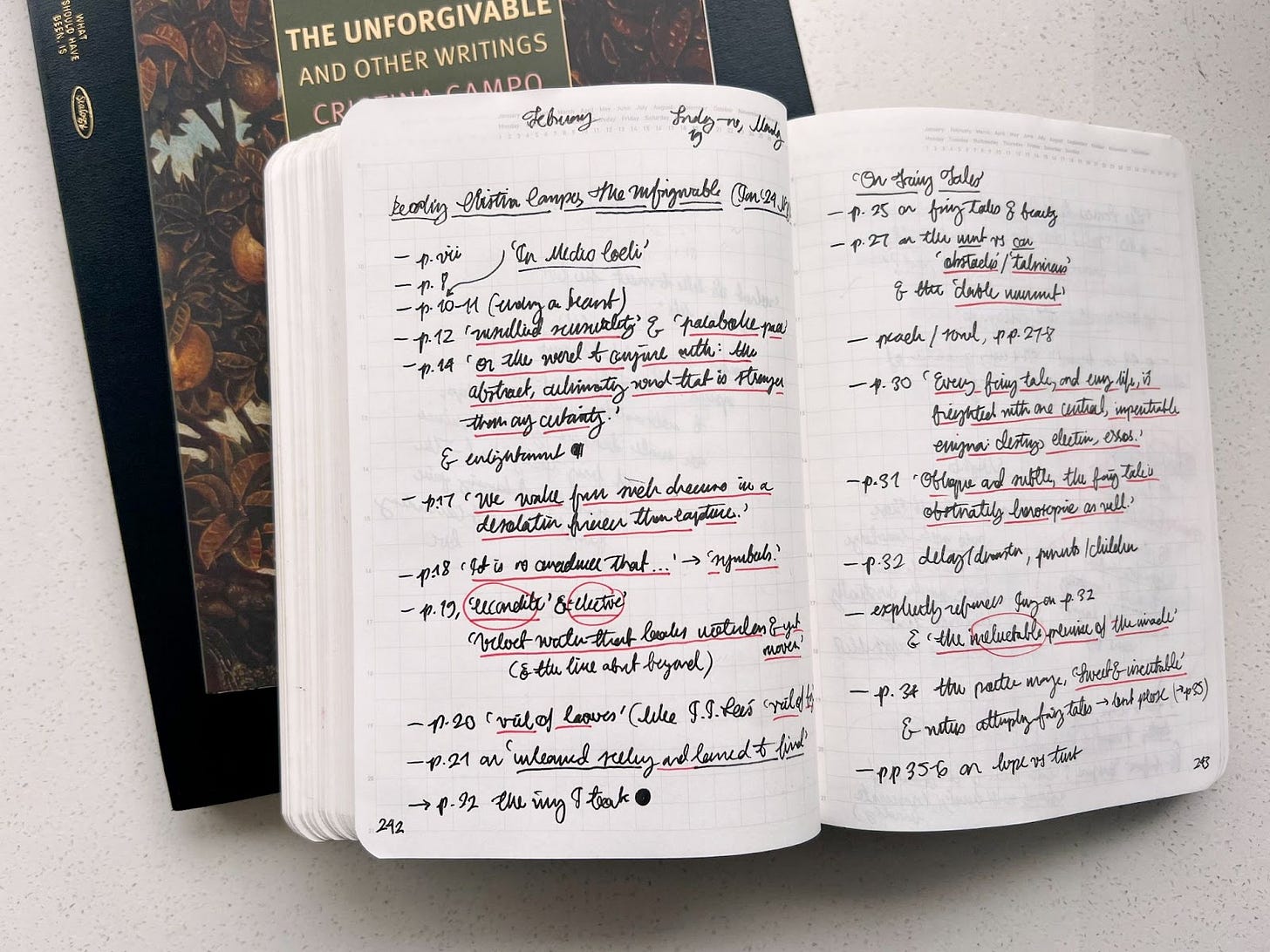

PKG: Before we even move on to Celine’s note-taking comments, can we just take a moment and admire how beautiful this notebook spread is?! Do we need a Notebook Porn series on A Reading Life?

Fundamentally, note-taking is something that should increase my appreciation or enjoyment of a book, or help me in my writing (either for my newsletter or the freelance criticism I do). Ideally, my notes will do both. But this philosophy means that it’s very important that notetaking doesn’t feel too laborious! And the goal isn’t really taking notes—it’s being able to think more clearly.

With that in mind, here’s what I do:

1| When I’m reading a book, I’ll highlight/screenshot passages (if I’m reading on my phone or Kindle/Kobo) or note down page numbers/quotes in a notebook (if I’m reading a physical book). If I write directly in the book, I’ll do so with pencil—but this is rare, because I try and keep my books as pristine as possible! Sometimes I’ll copy down quotes into a notetaking app in a very systematic way—especially if I’m writing a review essay on the book—but sometimes those highlights/screenshots/photos just live on my phone.

2| One of the best ways to remember material is to talk about it, so I’ll text friends little passages that seem funny or useful, and of course my reading roundups on my newsletter help too! Whenever I text a friend about a book, or I sit down to write a paragraph about it for my newsletter, I’m forced to think about the most beautiful moments or the most interesting insights from the book.

3| I use basically every app in existence—Notion and Apple Notes to copy quotes and write out summaries key ideas, Readwise to save highlights (which Luigi Mangione also used…) and I’m trying out a new app called Matter to help me read and notetake on newsletters and online articles/essays. I also love Zotero to keep track of research papers and PDFs.

A few years ago, I read Sönke Ahrens’s excellent How to Take Smart Notes, which describes a notetaking strategy that helps you produce more and better writing. The strategy is known as the Zettelkasten method and has a cult following online. I recommend it unreservedly; I also recommend finding a low-key way to practice it, because if you take the method too seriously, it becomes really time-consuming and stressful! Again: the goal is for notetaking to make reading more fun.

PKG: I co-sign on the idea that even though method and materials matter, the methodology should only be in service of the final goal. Do not create a perfect system that is impossible to maintain.

Are you particular about your materials - notebooks, pens, highlighters vs. pencils, etc?

I’m very finicky about my materials! I used to feel embarrassed by this, but then I came across an essay by the great German-Jewish intellectual Walter Benjamin, where he says: “Avoid haphazard writing materials. A pedantic adherence to certain papers, pens, inks is beneficial.” My pedantic attachments are the following: Stalogy notebooks (which I wrote about for the One Thing newsletter), a Sailor fountain pen with water-resistant black ink, and a red Sakura Pigma Micron pen.

How do you keep track of what you want to read?

I use Goodreads to track what I’ve already read and would like to read next. Whenever I hear about an interesting book—from a friend, or if it’s referenced in something else I’m already reading—I’ll add it on Goodreads and see if my library has an ebook available. If there is one, I immediately place a hold on it. I don’t always end up actually reading it—but I like being influenced by my instincts and the recommendations of other people I admire.

Where do you get ideas about what to read?

30% recommendations from people (both friends and people I admire online), 30% references in something I am already reading, and 40% books I placed a library hold on weeks ago and forgot about.

I’ll often develop the desire to become more well-read in a certain area. Like, I want to read more art history (after reading an essay collection by Olivia Laing, who writes so beautifully about contemporary art) or I want to read more Japanese women writers (after reading a novel by Banana Yoshimoto, who writes very touching and emotionally gratifying stories). In those cases, I’ll loosely set a goal or try to find specific books in that area, but I’m not very disciplined about it.

How do you decide what to read next? Are you a mood-reader or a planner?

I plan my reading—and then I throw away my plans, and read purely on instinct and impulse. Your question reminded me that, the year before I turned 30, I made a list of “30 (books to read) before 30,” and I only finished 6 books on the list. (One of them was E.M. Forster’s A Room with a View, because Zadie Smith had described it as “a young person’s novel…to have its largest effect, it’s best to read it as a teenager or as a young person.”) I had this beautiful plan, full of books that seemed notable and worthy—and instead I picked up books I’d seen someone mention on Twitter, books that I saw on Tumblr, books that a friend recommended…

I can only stick to my plans if I’m reading books for a specific writing project—and I like having writing things that push me to read books that have been “on the list” for months, sometimes years. Right now I’m reading Eva Illouz’s Why Love Hurts: A Sociological Explanation, because I want to write something about depressingly bad and toxic romantic relationships in novels. I’ve known about Illouz’s book for a while now, but it’s never felt like the right time to read it!

When people ask me how come I read as much as I do, I frequently just give them a list of things that I don’t do as regularly as I probably should: exercise, clean house, spend time with friends. What do you choose NOT to do in favor of reading?

I love this question, because I don’t think we acknowledge enough that choosing to do something means choosing not to do other things—and the best way to create a new habit is usually to break an existing habit, and create some empty space in life.

I read between 60–100 books a year. Reading this much means that I don’t use TikTok and my Instagram screen time is usually ≤10 minutes a day. I don’t believe in quitting social media entirely, but I do think you can get most of the value—staying in touch with friends, hearing about interesting events, keeping up with current events or pop culture discourse—by only spending a little bit of time on it.

Sometimes it’s not about quitting things, but finding things that complement reading. If I’m running on a treadmill at the gym, I’ll listen to an audiobook—or a podcast about literature, like the excellent LARB Radio Hour. Traveling by train is very conducive to reading, too; I finished volume 1 of In Search of Lost Time during a 9-hour train trip from San Francisco to LA.

I should also say that I don’t have children and I don’t have any caretaking responsibilities—that makes a huge difference! But the parents I’ve spoken to all say that, even though they have less time than before, they’ve also developed more purpose and intention in how they spend their time. If I do become a parent, I’m curious to see how my reading life changes.

PKG: Thank you for your note re: reading, parenting and caretaking. It always feels odd to complain about your own children but to paraphrase the great Cheryl Strayed — reading is all about concentration, solitude, and silence, and those are the three things that children are most not about.

Do you have any tips or advice for people who wish they were reading more?

1| Go on reading dates with yourself. I think it’s really lovely to turn reading into a special occasion, and treat it with some level of ceremony or reverence. Going to a café or restaurant or bar alone with a book, for example. When you treat something with care—whether it’s a person in your life or a particular hobby—it invests that thing with more meaning, and you’re reminded that committing to that thing is exciting, not an exhausting obligation.

2| Orient (some) of your social life around reading. I’m tremendously susceptible to peer pressure—I think most people are!—and I’ve realized that I can influence my behaviors by choosing the people I spend time with. Having friends who are intellectually curious makes me excited to read more. We can discuss our favorite books together, exchange reading recommendations, and reaffirm the value of reading to our private lives and to our relationship.

3| Read according to your own interests, not what you think you ‘should’ be reading. I’m paraphrasing the great writer and translator Lydia Davis’s advice here. In her essay Thirty Recommendations for Good Writing Habits, she says: Always work (note, write) from your own interest, never from what you think you should be noting or writing. Trust your own interest. Reading—and reading regularly—is easier to do when it feels genuinely enjoyable. A book that you feel you have to read (but don’t actually like) will never win out against the easy, anesthetizing entertainment of scrolling through memes on your phone. There are obviously great books that feel slow or boring at times—and in those cases I’ll try to push through to the exciting parts—but if I really notice that a book feels like a chore, I just quit.

4| If you spend too much time on social media, switch to reading-focused social media. Social media apps are often the enemy of reading, but not always. I honestly think that BookTok and bookstagram help people discover books and see reading as an exciting and desirable activity. In the same way that a social life (partially) oriented around books motivates more reading, I believe that a social media feed (partially) focused on books helps create that focus in your own life. Eventually, after scrolling through 20 images of people’s bookshelves, you’ll start feeling bored by all the content and put down your phone to go look at your bookshelf.

PKG: This definitely works for me. In fact, this kind of social scrolling produced so much productive fomo in me that I started this very newsletter. 😂

What are you reading now and what is one book that you find yourself recommending to people over and over and over again?

There are 4 books that have genuinely changed my life and how I think:

1| The novel that permanently changed my perception of fiction as self-indulgent and irrelevant to a “serious” adult life was the Norwegian novelist Vigdis Hjorth’s Long Live the Post Horn!, which is about a depressed woman who feels sick of her office job, sick of her shallow and distant relationships with other people, and generally sick of her life. What’s special about this novel is she doesn’t actually end up changing her entire life in order to be happy. Instead, she discovers that there’s a lot of purpose and meaning in her job after all—she begins working on a PR campaign for the postal workers’ union, and discovers how special it feels to be involved in a collective effort to improve people’s living standards and well-being. And she learns to open up to her boyfriend, which helps them both feel less lonely and more understood. Hjorth is very easy to read and very profound; she is one of my favorite living writers.

2| In 2022, I decided that I would read Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, a great modernist novel that’s over 4,000 pages long. Reading it was such a project—but I’m very happy that I devoted most of my year to Proust. The novel follows a young French man from his childhood in the idyllic village of Combray, to his early adult life in Paris where he falls in love with various society women and aristocrats, to his old age, where he and his friends grieve the violence and death of WWI. Throughout, Proust writes about art and love and the burning desire to write—and the equally urgent desire to procrastinate, and throw oneself into parties and gossip and frivolity instead—in extremely beautiful, extremely long sentences. Proustian sentences seem to skip from past to present, from literary reference to scientific metaphor, in an astonishingly nimble way.

3| The architectural theorist Christopher Alexander’s A Timeless Way of Building is one of those cult classics that transcends disciplines. In it, Alexander tries to understand why certain buildings have a particular “quality without a name,” which makes people feel most at ease, most serene and alive and present in the world. It’s an elegantly written book that made me see the built environment in a new way. It’s also had an enormous influence on software designers and computer scientists.

4| One of my more embarrassing traits is that I love self-help books, and I especially like self-help books that touch on one of the most vulnerable but important ambitions of my life: to be in touch with great cultural works (books, art, music, objects) and be able to create cultural works myself. Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way is a little bit woo, and which turns a lot of people off—but it is also the book that actually made me take myself and my writing seriously, and the journaling approach she recommends has been so helpful! It’s one of the most psychologically insightful books I’ve ever read, and it’s really useful for people who want to write and make art but are too afraid to start.

Some questions for you:

Which of Celine’s tips and ideas resonate the most with you?

It was fascinating to read how much Celine’s taste in reading has changed over the years. Do you recognize similar patterns in your own development as a reader?

Celine mentions so many great books and essays. Which one are you tracking down first?

This was such a lovely interview, thank you! Long Live the Post Horn! is now on my TBR. And I so agree with Celine about The Artist's Way, it made me finally take my creativity seriously.

My two favorite substack writers together! Really loved this interview, thank you Petya. Loved reading about Celine’s book dates, vacation reading, notetaking, reading history, everything. It’s just so great to read about other people with a similar reading obsession, it makes me feel happy and connected. I am currently in the middle of a big chronological Virginia Woolf project, but looking forward to reading Proust (have read a bit and LOVED it), Middlemarch and more literary criticism. Now that I think about it, I loved Proust so much that I am avoiding reading it, because it can’t face the thought of not looking forward to it anymore. Let’s see if I can get around that!